Alpinism starts as a game, and firms into a story in which your heroes die and you might too.

I played from 2014 through 2018 and during that time I had many close calls. Since then, I’ve lost three close friends to the mountains. In 2018, I was forced out of play when I shattered my right femur (not while climbing). I have not checked back into the game in the six years since my injury. First, because of loss of function, and now, because I am scared. I am scared, because alpinism is totally fucked.

When I was just starting, I followed a framework for success. I climbed a lot. I developed a training plan and worked hard at it. I got grants. I Instagrammed. I got a few sponsor-ish deals. With all that hype, I thought to myself that other people cared that I did this stuff, and early on in my success I wrote, “Suddenly, there were other people out there, people I didn’t know, who thought that I could do this. That I should try it.” For the love of the sport and the love of the likes, I believed this story and hit the throttle.

So, I edged into a world I will never forget, one where people go to places they surely don’t belong. For so many reasons, the world of alpinism is addictive. It is kinesthetic and maximally sensational. It all feels very big. It is, in fact, very big. On a flight out of the Alaska range after my second season of climbing and guiding, I vividly recall looking out of the plane’s window thinking, “We should turn this thing around.” I was high on adventure, adrenaline, and awe — I couldn’t stay away.

In retrospect, a huge part of that high was how I felt when I viewed myself within the context of adventure, adrenaline, and awe. I cultivated an identity. When I began to broadcast that out into the world, I stepped over a line from the love of the game, into a love of my ego.

Out beyond the edges of my ego, I was standing in a desert of human experience — in reality, it is you, a handful of friends, and a sliver of humanity beyond that cares what you do, and how or why you do it.

Today, most people who follow alpinism do it via social media. Folks swarm up for the glory shots which accumulate likes and kudos. And what follows are the shiny goods — clothes and shoes and climbing widgets. People love their gear. All of this packaged into slick magazines, publications, and films. You can almost smell the sex appeal.

Now, I’m not about to decry capitalism or outdoor brands broadly. For many reasons, I like well-regulated capitalism. Gear companies need to make money, and athletes supported by those companies need to make money too. The fair exchange of goods and services is a necessary part of modern life.

However, over the past twentyish years the grand reinvention of human communication (i.e. the advent of the ‘virtual’ life parallel to ‘real’ life, and the constant decision to live in one over the other) has piled on financial and social incentives to every adventure sport, including alpinism. Like most other human endeavors, adventure sports have been caught up under the overwhelming crush of limbic capitalism. Today, eyeballs pay the salaries of most branded professional athletes. And generally, the more eyeballs someone draws, the higher their paycheck.

At one point, I wanted that life. Today, I definitively do not. In the rest of this essay, I’ll highlight four stories I believed from 2010 to 2020. These stories contributed to my assessment of mortal risk-taking as a worthwhile moneymaking endeavor. They alone did not cause me to act — but they certainly changed how I thought.

But first, what does it mean to “be fucked?”

TOTALLY FUCKED

Though I didn’t know him personally, Kyle Dempster was my hero. I looked up to his general demeanor and his impressive list of ascents, and read and watched as much of his storytelling as I could. I really admired his spirit of adventure, particularly well-captured in “The Road to Karakol” which I watched maybe fifty times.

In 2015 I wrote to Kyle, looking for beta for my first trip into the Alaska range.

Hi there Kyle,

Got your info from my buddy Austin. I've got a couple of AK-related questions that I think you might be able to answer - if you're willing!

First, I'm flying onto the Kahiltna on 4/21 for my first trip to the Alaska range - woo hoo! My partner and I have gathered a lot of info on the Bibler-Klewin from friends in NH, but we're looking for more info on Deprivation. I heard that you've done Deprivation. I wonder if you have a route description, trip report, or (most hopefully) a topo for the route?..

Thanks for any info you can share!

Rock on,

Jimmy

Kyle’s reply:

Certainly willing!

Bibler-K is def the better route! Deprivation is, honestly, a pretty mediocre route. At least in the conditions we found it. 90% of dep is really easy/cruiser low angle snow climbing. 5% of it is fun steeper ice. and another 5% is TOTALLY FUCKED sketchy and steep snow/snice climbing. Truly fucked is this one pitch down lower on the route. It is the Crux for sure. Maybe it's better in better conditions, but honestly dude, not psyched on how dangerous that pitch felt…

Looking forward to meeting ya. And feel free to fire away with your questions.

Kyle

For a situation to “be fucked” is a binary. It is to be wrong and unacceptable. Of all the times I’ve used the phrase, it has always meant “if I do this wrong, I am going to die at this moment.” Or, if something happens that is out of my control in this moment, (rockfall, avalanche, etc.), I will die.

Kyle died while climbing in Pakistan in 2016. Before he died, Kyle wrote an article called Student of the Game: “As a student of the game in a classroom that is deadly, I know that sharing our experiences and our blunders helps to further educate and keep our class alive.”

Of course, we’re all terminal. That is part of being human. That aside, everyone I’ve known who’s died in the mountains said some variation on “I’d rather not die in the mountains,” and then died in the mountains. I think of how many times I said that exact thing when I look back at my own register of close calls:

“Daggers of glacial ice hung above us. The moat pinched into a gully then and opened up again. I saw some (not small) rocks fall close to my right, through the pinch. I drilled a thread as Mike descended. ‘Dangerous spot, move fast,’ was the extent of our conversation.” (Alaska, 2016)

“I planted my tools into the hard snow, sat down against the tethers that bound me to them and prostrated myself before [a block the size of a microwave as it] ‘whizZZ‘[ed] from above... The boulder exploded immediately above, and sparks and the acrid scent of rockfall whooshed around and past us.” (Patagonia, 2017)

“Ethan was following, approximately 15m into the pitch, when a snow mushroom the size of a VW bug fell and strafed the couloir below. It fell below our belay spot; we had avoided a direct impact by ~1 hr.” (Canadian Rockies, 2018)

In each of those situations, I could have measured my salvation in feet or by minutes. We were climbing in places that were inherently dangerous, as though passing corridors where a gunman randomly shot at untold intervals. Much risk can be managed, for example by choosing not to climb where rocks and ice and snow mushrooms can fall on you, in good weather conditions, and so on. But then, you still must execute perfectly — no falls, no slips — no mistakes. Humans make mistakes. Ergo, Alpinism is fucked.

STORIES I TOLD MYSELF

Which brings me to the stories I told myself, that aren’t true for me anymore.

Story #1: Social media is “necessary”

When I started doing bigger climbs, I also started Instagramming. Other climbers were doing it, as it is a simple storytelling platform, and those who were particularly capable were squarely in the crosshairs of brands. At the time, I wanted to be there too (see Story #2).

But instead of actually telling stories (or in today’s parlance, “creating content”), I would spend a lot of time scrolling mindlessly, or in targeted ways, and comparing myself and my climbing accomplishments to others’. Before I deleted my Instagram in 2017, I was living probably quarter-time in the virtual world. Every time I shared something out into the void, I hungered for the metrics that returned. I would go about my day twitching to check for likes and comments.

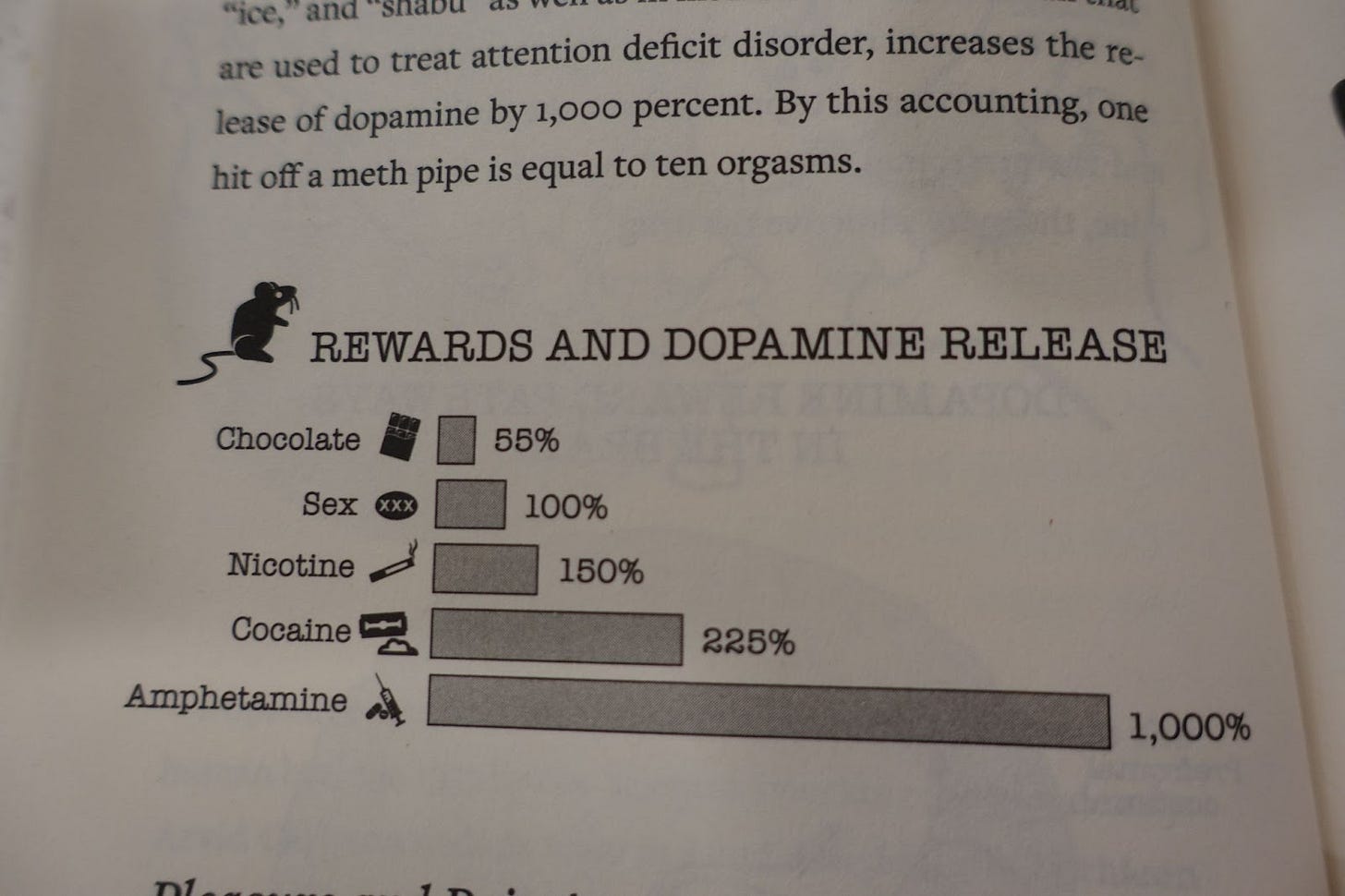

Social media rewires people’s brains in ways we are just beginning to understand. With Instagram and Strava, smartphones become tiny stages reaching massive audiences — I’ve heard them called ‘ego machines.’ Virtual engagement bathes brains in dopamine, stimulating neurochemical feedback for ‘more me,’ not dissimilar to feedbacks for chocolate, orgasms, ciggys, and hard drugs.

What I did not understand about myself in my mid-twenties, is that I have strong addictive personality traits. At various times I have been addicted to books, writing projects, work, exercise, and video games.

So, when I was digitally bathing in imagery of epic mountain landscapes and hardcore climbing, cocaine rat really worked overtime in my brain. I constantly thought about taking my own photos of epic mountain landscapes and hardcore climbing -- not for the memories, but to share on Instagram. I bought a camera for social media, because I wanted to be a pro-ish climber and I thought this was necessary.

Today, I still use social media on occasion. But my relationship to social media is more akin to my relationship to the 19 cigarettes I’ve smoked in my life — I try to use it precisely.

The addictiveness of adventure combines with the addictiveness of social media platforms to produce a potent cocktail, and I believe this mix changes humans’ moral behavior and risk-taking frameworks in powerful and poorly understood ways. So, to young Jimmy, I’d say, “Take care, as social media will rewire your brain. It will change the way you think about what’s right and wrong for you, and it’s easy to get carried away.”

STORY #2: I should seek sponsorship by a brand to make money

Branded athletes are a unique type of salespeople. Sales is a core part of the job, which Nick Paumgarten captured well in a 2020 New Yorker article:

“The panel that afternoon [at a North Face athlete retreat], featuring Tate [a grief counselor], me, and a social-media guru, was on “storytelling.” What did I know about the kind of storytelling that they were there to ponder—the framing of their adventures, which they refer to as projects, in such a way as to secure funding, attract an audience, and burnish a brand? It is the job of a professional adventure athlete to create media: films, photos, articles, social posts. You go out and perform amazing feats in amazing places while wearing the amazing gear. The framing and the depiction of these feats give them scale, reach, and meaning—and commercial viability.”

I have a mental model, a 2x2 in which ‘outdoor athletes’ exist on a spectrum, from Olympian to NARP (non-athletic regular person), and good to bad at sales. Take a look.

In my framing, there are two main ways to create value. Be a better athlete (and let your accomplishments speak for themselves) or be better at sales. For sales, storytelling seems less important in a time when sci-fi has become reality. Rather, we’ve evolved to a place where personality makes the big bucks. Hence, the rise of the influencers.

In retrospect, I don’t know why I wanted to make money from outdoor brands. But I did, and I tried to get there. I didn’t get very far, and felt kind of icky with how far I did get. Looking back, here’s what I’d tell young Jimmy: “The bottom line is, when you exist in an environment where you are incentivized (via money and exchange of goods) to create media based on risky athletic feats, either your feats or your media must carry what you owe. If you still want to do this, and your media is carrying, figure out how to do it in a way that feels authentic to you and good for your soul — but be open to the chance that this may not be possible for you.”

Today’s brand expectations get a lot darker than for social media posts. I recently spoke to one professional athlete who shared that their sponsor offers “send bonuses” to their alpinists, which are direct financial incentives to do hard, dangerous climbs — a lot different than a salary for your general vibe and accomplishments and social media aptitude. It's more like a paid round of Russian roulette. Perhaps this is the outdoor industry’s grandest expression of late-stage capitalism — “we demand eyeballs, you supply them — through glory or death.”

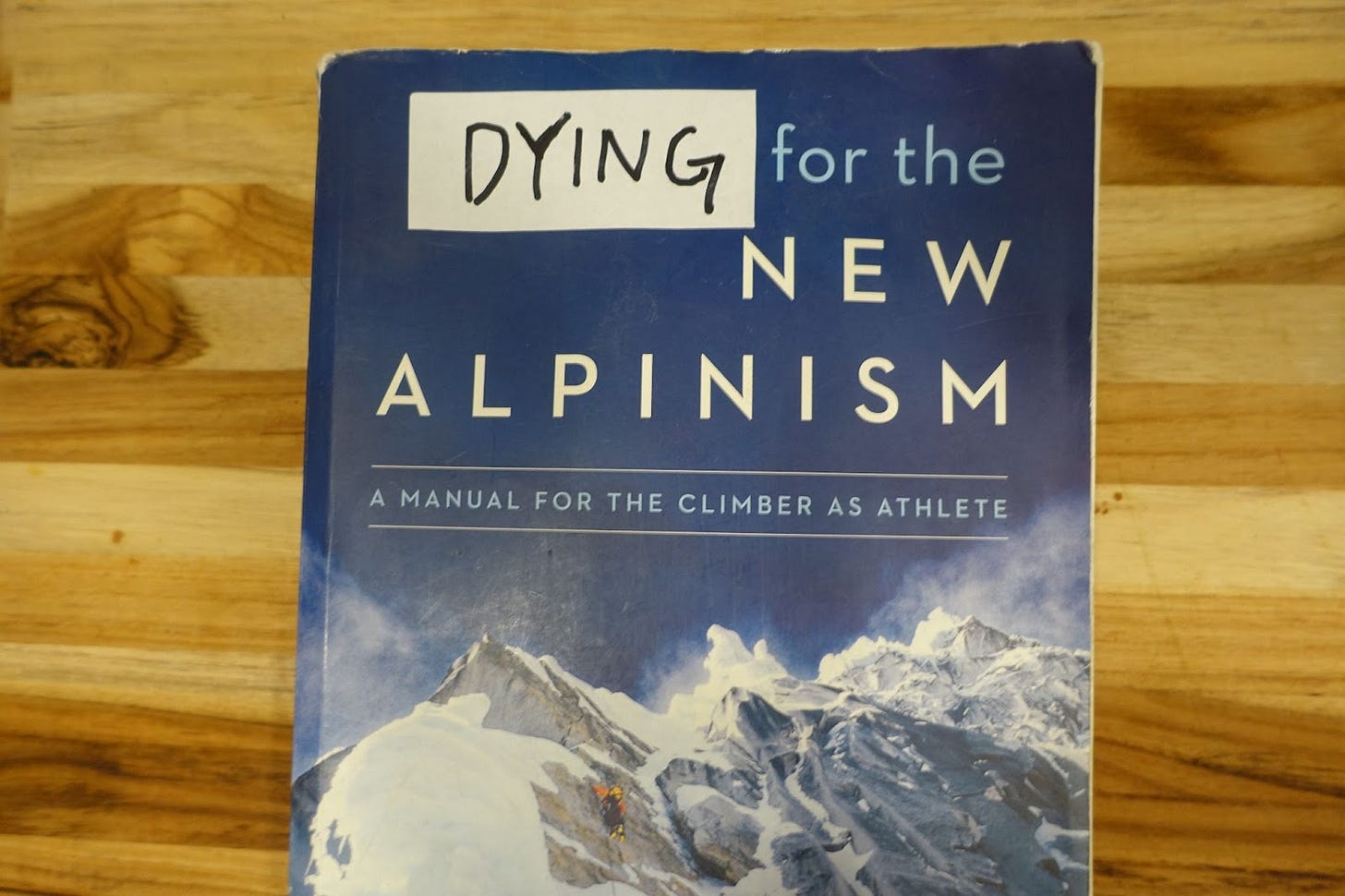

STORY #3: There’s wisdom in hardcore climbing training literature

In 1999, Mark Twight published a book called Extreme Alpinism: Climbing Light, Fast, and High, which established a hardcore, minimalist climbing ethos. Twight writes in aggressive prose, and his words pulse with testosterone. A couple of years after I started ice climbing, I devoured Extreme Alpinism and Twight’s book Kiss or Kill, and the literature of his peers who shared a similar “a muerte” attitude (including Steve House).

So I was thrilled to read Twight’s introduction to Steve House’s 2014 book Training for the New Alpinism, the modern bible of training for climbing. It summarizes his writing style well.

My approach to training echoed how I climbed. The romance of climbing didn’t interest me. I didn’t seek harps and wings. I heard no opera up there. Instead, my mountains had teeth. The jagged edge we walked up there dragged itself across my throat, and the throats of my friends and peers. I took the mountain’s indifference to life as aggression, and fought back. I armored myself against that indifference; with training, with thinking, with attitude. I trained with friends who shared a similar approach. Our mantra was dark, but it motivated us.

When we ran we breathed in rhythm -- no matter the speed -- and that beat had words: “They all died.” We inhaled and exhaled the great alpine epics… to push ourselves to a place where we would never come up short, physically.

The consequences of falling short made training important. I realized early that controlling the things that I could control gave me greater freedom to address the things that I could not control. And the mountains offered those in spades. (13-14)

As a young climber, I ate this stuff up. I gushed about it to my climbing partners. My admiration was not unique. Kyle, writing in Alpinist 42, professed an early devotion to Extreme Alpinism.

I studied Mark Twight’s Extreme Alpinism with the same devotion that a monk strives to connect with God’s purpose. I didn’t just want to respect Twight and his tribe. I wanted to embody their knowledge. As The Book instructed, I took my training journal to the crag. I tallied every pitch I climbed, noting what felt right or wrong and what I needed to work on. At the gym, I punished myself under the weight of heavy barbells. I documented each rep to quantify improvement. I quoted Twight’s bible with unwavering faith: “The harder you are to kill, the longer you will last in the mountains.”

Feeling strong after training is an amazing feeling. In 2018, I hired a coach to help me prepare for a trip to the Waddington range that I never got to go on. My effort paid dividends. At one point I emailed him, “There’s no doubt that the training I’ve done in the past four months has helped me out immensely. I felt stronger on the approach, fresh leaving camp, and had no doubts about my physical capability when we got to the difficult climbing.“

It’s not at all incorrect to describe training in terms of ‘making yourself hard to kill.’ The thinking goes, if you’re fit, you can spend a hell of a lot less time in places that are likely to kill you, thereby reducing the chance you will be killed. It makes a lot of sense.

Rather, I think a problem with Training (and Extreme Alpinism), is that it presents this material as front matter. The foremost training methodology for alpine climbing today starts with a treatise on hardening yourself to Death. At least in Training, the ‘why take the risk?’ section is relegated to the last few chapters -- mere afterthoughts.

Later on in his Alpinist 42 article, Kyle described his recovery after a close-to-the-edge solo attempt on a wall in Pakistan:

During my six-month recovery, I shelved Extreme Alpinism. I realized The Book was someone else’s story. It didn’t have to be mine. Although I held on to some of its ideals, I returned to a more-lighthearted approach. Alex Lowe’s adage echoed in my thoughts, “The best climber in the world is the one having the most fun!”

Couldn’t agree more, Kyle (and Alex), couldn’t agree more. So to young Jimmy, I say “Knowing your why is most important. Take all climbing writing with a pound of salt. What’s true for others may not be true for you. ”

Which leads me to my final story…

STORY #4: It won’t happen to me

With all of this, I told myself, “I will train hard. I will make myself invincible.”

That is a fallacy.

In the same email to my coach (Story #3), I wrote: “There were several scary moments on the route. I want to proactively monitor threats like snow mushrooms and think about roping up over schrunds before charging ahead. I want to add these elements into the decision-making framework [I’m developing]... Increasingly I see value in systematic risk-assessment.”

Again, Kyle in Student of the Game: “‘I nearly died...’ [and now] I’m grateful to have learned. And because of that lesson I’m now a safer climber… As a student of the game in a classroom that is deadly, I know that sharing our experiences and our blunders helps to further educate and keep our class alive.”

See the parallels? I do, now.

So, young Jimmy: “You may die in the mountains. If you play, accept it as a fact. If you are thinking that you won’t, you’re no longer living in reality. You may want to stop climbing until you come back to Earth.”

AND YET

When I am having a hard time and I doubt myself in the world, I close my eyes, and think of standing atop the Alaska range. Through visions of blue and white, the warmth of sunshine and the chill of icy air, I recall all that I and my partners have endured to get here. These memories are acid-dreams, embedded in my marrow. They summon to mind absolutes of love and trust for myself and my closest friends. I wouldn’t give them up for just about anything.

There is a story about Abraham Lincoln which I’ve grown to love. It goes something like this — when he was angry, Lincoln would write a letter. Then he would put that letter in his desk drawer. If he woke up the next morning and was still angry, he would send the letter. If he wasn’t — he would burn it in his hearth.

I take it to mean that timefulness and reflection and an ability to step outside oneself are most important qualities for a man to possess. All things that modernity, in its current state, depletes.

So no, I wouldn’t tell young Jimmy to avoid taking risks. I wouldn’t tell him to stop climbing mountains if deep down, that was what he felt drawn to do. Instead, I’d finish my soapboxing with this:

“Think about it. Why -- really why -- do you want to climb mountains? Write the answer down.

Take three months entirely off social media. Then come back to it and ask, again,

Why -- really why -- do you want to climb mountains?”

Pete -- just emailed you. Sorry to learn about Balin, and glad you reached out.

Landed here while trying to pull thoughts together about Balin Miller today. I can’t say I follow alpinism anymore but just felt some reflection of my earlier self in him. And one of those trips of mullet-clad young men dropped off on the Kahiltna. Need to find where you’re at some day and reconnect!

Peter M